Growing up in the Armenian Apostolic Church was a sensory delight, with its flickering candles, rich colors, sparkling gold, and the sonorous chanting of priests and songs of the choir – all shrouded in incense, ritual, and mystery. So powerful are these memories that it felt only natural to turn to this heritage to find a research topic for my aromatherapy certification.

Many of Armenia’s aromatic and medicinal traditions date back nearly three millennia, and still today, herbs and oils can be found in Armenian pharmacies alongside more conventional pharmaceuticals. These traditions also form the basis for the creation of the Armenian church’s holy oil, in a process that takes place every seven years and has done so, unbroken, for more than seventeen centuries. This sacred anointing oil, or Holy Muron, is a complex infusion of oils and aromatics created in the heart of Armenia and shared with Armenians around the world. (The term ‘muron’ comes from the Greek myron, which is the fragrant oil holding the highest degree of sanctification in the Eastern Christian church, used only for baptism, ordination, and consecrations.)

History

Herbs and aromatics have played a central role throughout the South West Asia and North Africa (SWANA) region and the Mediterranean for millennia, helping to nourish, inspire, beautify, and cure. This is grandly illustrated, perhaps to an extreme, in the case of Mithridates VI who lived between the 2nd and 1st centuries B.C. and inherited the rule of Pontus, a Hellenist kingdom in Asia Minor, following the assassination of his father. As a safeguard against the possibility of Mithridates’ own assassination, his court physician is said to have created a prophylactic antidote containing almost all the known spices of the day: costus, iris, cardamom, anise, nard, cassia, silphium, styrax, castor, frankincense, myrrh, cinnamon leaves, and bark, galbanum, saffron, and ginger. The antidote was reputedly so effective that when Mithridates tried to poison himself to avoid capture, he was unable to do so. Known in English as Mithridate, it is believed to have been a ‘universal antidote’ that could counter any type of

poison. (1)

During this same period (2 nd cent. B.C.) in neighboring Armenia, King Vagharashak initiated the cultivation of medicinal plants in special gardens. Some plants were so highly valued for their curative properties that expressions of their worship can still be found in ancient folklore. In Armenian temples, priests who had mastered the art of folk medicine helped to heal the sick, often using infused and aromatic oils.(17) It was well known at the time that it was the spices and herbs that made the healing balms and oils effective, and medicine could not have been imagined without its aroma.(12) When Armenia adopted Christianity as its state religion in 301, monasteries

were founded at the sites of the ancient temples, which also served as early hospitals.(17)

Aromas were also an integral part of ceremonial and sacrificial practices throughout the ancient world. Flowers, wreaths, and perfumes adorned altars and statues, and incense was burned along the routes of ritual processions, demarcating sacred spaces, actions, and identity. These aromatics, particularly in their role as a major ingredient in incense, were an early forerunner of aromatherapy. Traveling via the smoke that was intrinsic to these ritual practices, aromas seemed to pass from earth to heaven and fragrance became an attribute of the divine. Even today, in addition to its sacred significance, the Armenian Holy Muron is believed to possess healing and medicinal properties.

In the ancient world, perfumes and incense were valued based on the number of ingredients they contained and complex compounds signified exceptional worth in both value and effort. Ancient Egyptian texts contain references to a range of aromatics including frankincense, myrrh, cedar, balsam, pine, myrtle, benzoin, labdanum, mastic, juniper berry, cardamom, and calamus, many of which were ingredients in Kyphi, a perfumed substance used extensively in temples. Echoing this is the recipe for Ketoret, the Jewish incense used to prepare the temple for worship and outlined in the Talmud as “balsam (or stacte), onycha, galbanum, frankincense, myrrh, cassia, spikenard, saffron, costus, aromatic bark, and cinnamon”.(2) In that same spirit, the original Holy Anointing Oil outlined in the Old Testament was made up of pure olive oil and four aromatics: myrrh, cinnamon, cassia, and calamus.(12) Over time, medicine and worship mingled, oil became a symbol of divine healing powers, and anointing became a sacred act of faith. The effects were believed to include both physical and spiritual healing and the restoration of wholeness and well-being.(5)

The Muron

Influenced by this ancient aromatic world, Armenian Holy Muron contains forty-eight different components, derived from an array of flowers, leaves, grasses, roots, rhizomes, fruits, seeds, woods, and bark. According to tradition, a portion of the Holy Anointing Oil originally blessed by Moses remained in Jesus’ time. Jesus blessed it as well and gave some to the Apostle Thaddeus, who took it to Armenia and healed King Abkar of a terrible skin disease. Thaddeus is said to have buried a bottle of the oil under an evergreen tree, where it was later discovered by Saint Gregory the Illuminator, who mixed it into the first Muron he created and blessed in 301. To this day, whenever a new batch of Muron is prepared, a portion of the old one goes into it, so it always contains a small amount of the original oil blessed by Moses, Jesus, and Gregory. This continuity factor is highly revered in the Armenian church.(13)

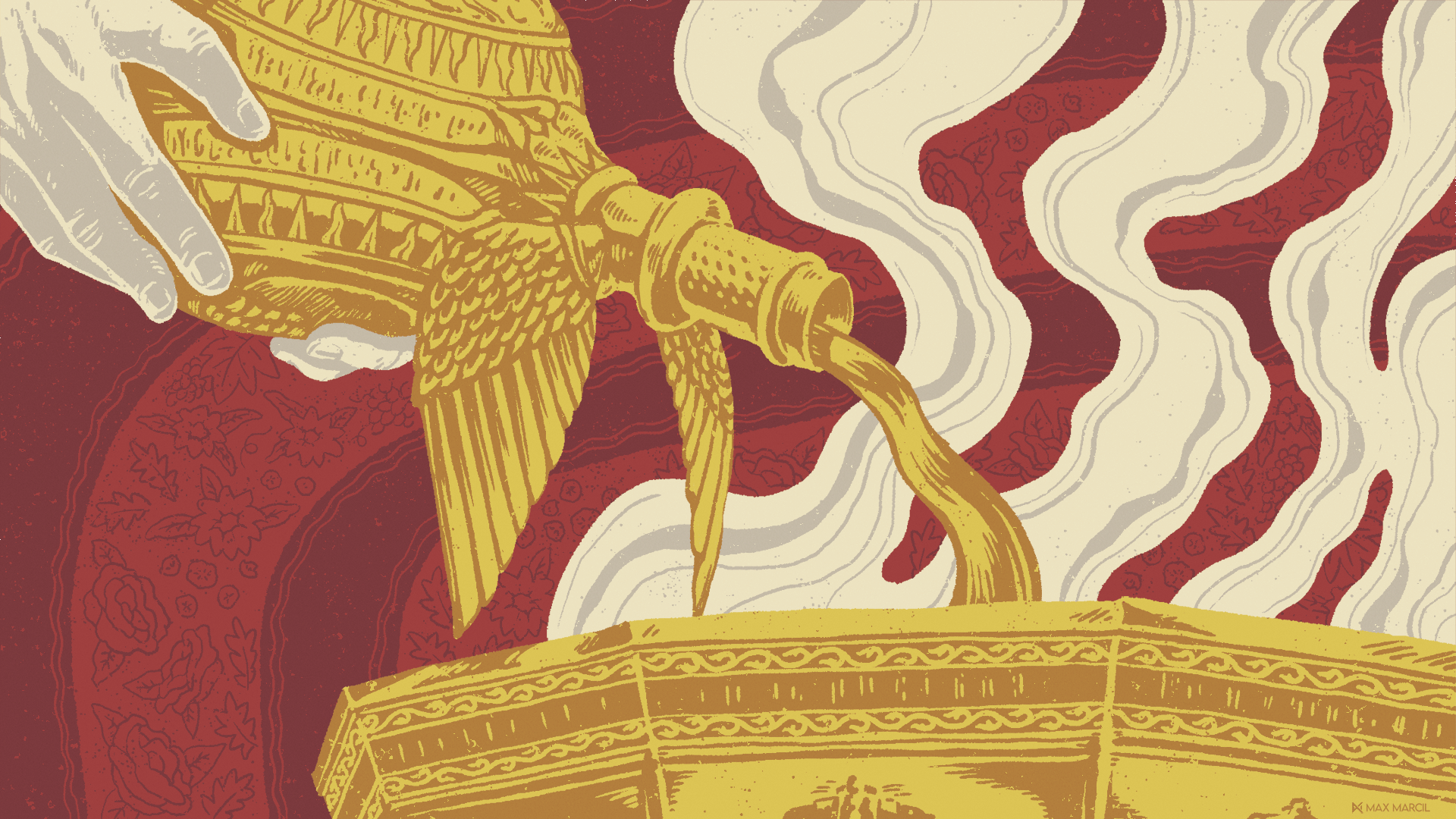

The making of the Muron begins months in advance with the gathering of ingredients from various parts of the world. Each ingredient is crushed and ground by hand, and precise quantities are blended in a large cauldron of pure olive oil. The lid of the cauldron is sealed with uncooked dough and it is placed into yet another larger cauldron filled with water – a double boiler of sorts. The entire mixture is heated and steamed for three days and nights, tended around the clock by

the Priests of Holy Etchmiadzin.

At the end of the infusion process, the mixture is carefully strained of solids and placed in a ceremonial vessel, where it sits on the altar for forty days, “so it can receive the prayers, psalms and hymns of everyday life.” (11) On the day of its blessing, a small amount of Muron from the previous ceremony is added, continuing the unbroken chain begun by St. Gregory the Illuminator more than 1700 years ago.

In 2001, the Muron ceremonies took place in the Armenian Holy See of Cilicia in Antelias, Lebanon, and the process was documented by filmmaker Nigol Bezjian.(4) Simply titled “Muron”, this award-winning film beautifully illustrates the Armenians’ strong sense of community, tradition, and faith. Priests and parish members worked side by side measuring, mixing, tending, and praying; all while reveling in the remarkable aromas.

The Ingredients

Although a complete list of the Muron’s ingredients is readily available in descending order by proportion, the botanicals are identified only by their common names and some of the translations from the original Armenian are debatable. Thus, armed with my trusty Armenian dictionary, I began translating, triangulating, and following threads with the goal of identifying each component as accurately as possible. A complete list of the ingredients is included in the Appendix along with my notations, and the following is a deeper dive into some of the more interesting components.

Resins

The base of the Muron is a mixture of pure olive oil and balsam. The term ‘Balsam’ can encompass a wide range of aromatics, however, in this case, it is most likely Commiphora gileadensis, sometimes known as the Balm of Gilead or Balsam of Gilead, and in the same genus as Myrrh (Commiphora myrrha). Renowned for its aroma, this resin is recognized in ancient medical texts for its exceptional curative properties and research supports the presence of beta-caryophyllene offering a broad range of therapeutic benefits, including anaesthetic, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antitumoral.(2)

As with the Egyptian Kyphi and Jewish Ketoret, Armenian Muron contains multiple resins as well, lending it a tranquil, soothing, and spiritually supportive aromatic quality.(14) In addition to Commiphora gileadensis, the other resinous compounds include Incense, Styrax, Olibanum, Crystal Tea, and Mastic. Through a process of elimination supported by research, I concluded that Incense is Styrax benzoin, Styrax is Liquidambar orientalis, and Olibanum is Frankincense or Boswellia sacra.

Crystal Tea

Crystal Tea was a mystery – until I focused on its Armenian name ’ladan’, which led me to Ladanum, generally recognized as Cistus creticus. A few different species of Cistus are common in the Mediterranean and the leaves and twigs exude a musky-sweet, sticky brown resin which emits a noticeable fragrance on hot days. Also known as Rock Rose or Rose of Sharon, the Ladanum of ancient times was most likely a mixture of species because the resin was combed from grazing animals – either the fur of sheep or the beards of goats.(8) The traditional medicinal properties of Cistus creticus have been validated in scientific research and it is regarded as a tonic, antifungal, and wound healer.(2)

Mastic

Popular in Ancient Egypt, Mastic is Pistacia lentiscus, a broadly spreading tree with a thick trunk. The wood is hard and white and its dense foliage casts a heavy shade, providing welcome respite from the hot desert sun. When the bark is cut, a sort of turpentine emerges and exposure to the air solidifies it into a transparent gum. Dioscorides suggested that the turpentine was antidotal, aphrodisiac, diuretic, and expectorant.(8) Few resins have a greater range of applications in medicinal folklore than this, which was used for calluses, carcinomas, cysts, fungoids, polyps, sclerosis, skin ailments, and tumors. The leaves of Pistacia lentiscus have been used as an emmenagogue and for diarrhea.(8)

Roots and Grasses

Departing from the resins, the 13th and 14th on the list of ingredients are Hors Elder and Camel’s Hair – both unfamiliar terms, with Camel’s Hair perhaps being the most challenging.

Camel’s Hair

Although it could, in fact, be the hair of a camel, it seemed unlikely that the Muron would include a component of animal origin. A consultation with Rev. Father Vart Gyozalian of the Armenian Apostolic Church in Ward Hill, MA confirmed my suspicion that it is indeed a botanical. The Armenian term finally traced back to Camel Grass or Camel’s Hay, and Duke’s Handbook(8) identifies it as Palmarosa (Cymbopogon martini). Aromatic grasses, like Cymbopogon martini were used so much in Ancient Egypt that, when they opened the tomb of King Tut approximately three thousand years after burial, the aroma of Cymbopogon was still obvious.(8) The grass is used in Ayurvedic medicine to treat neurological disorders and boost the immune system and energetically, it is uplifting, soothing, and helps to create a sense of well-being.(2)

Hors Elder

A Google search turns up a great deal of information about horses. It is, however, a traditional Armenian medicinal – Elecampane or Inula helenium, part of the Asteraceae family along with sunflowers and ragweed. There are a few differing opinions as to the origins of the Latin name, many of them relating in some way to Helen of Troy. Another common name for the plant is Horseheal, most likely springing from a belief that it cured the skin ailments of horses. In Britain, it is known as Elfdock or Elfwort and thought to be a favorite of the little people. The roots and rhizomes have been used to treat gastrointestinal distress, whooping cough, and yellow fever(10) and research supports the therapeutic properties of Inula helenium oil as antiseptic, anti-inflammatory, and immune boosting.(9)

Leaves and Flowers

Hazelwort (#15)

Refining translations from the original Armenian, Hazelwort became Allheal, sometimes also called Heal All and more specifically, Prunella vulgaris. With an ancient history of use in herbal medicine, it is perhaps best known for its wound-healing ability and benefits for throat infections. The essential oil has astringent, anti-inflammatory, and antiseptic properties.(9)

Laurel (#21, #24 & #25)

Perhaps best known as a Greek symbol of triumph and achievement, Laurel (Laurus nobilis) is an evergreen shrub or small tree and a relative of sassafras. The leaves are used to produce essential oil. The entire plant is aromatic, however, and the leaves, flowers, and seeds are all included in the Muron. The flowers are greenish and small, and shiny, black, fleshy fruits are produced in the Fall. The medicinal value of Laurus nobilis has been recognized since ancient times. Galen recommended it as a diuretic and liver stimulant, and the essential oil has multiple therapeutic properties, including analgesic, carminative, antispasmodic, and expectorant. Energetically, Laurel is uplifting and stimulates inspiration, insight, and creativity.(14)

Myrtle

Also rich with symbolism, the evergreen shrub Myrtle (Myrtus communis) has been grown for millennia for its fragrant flowers, leaves, and bark. Its small white flowers appear in large numbers in the middle of the summer. The resulting fruit is a small berry, resembling a blueberry, which is sometimes used in northeast Syria in the preparation of an aperitif. The entire plant contains fragrant oil and all of its parts can be dried for perfume.

For the Greeks, Myrtle represented love and immortality and to ancient Jews, it was symbolic of peace and justice. Arabs say that Myrtle is one of three plants taken from the Garden of Eden because of its fragrance. During Muslim holy days in Syria and Lebanon, Myrtle branches are placed on the graves of loved ones. In Turkey and Russia, the bark and roots are used for tanning leather.(8) The essential oil of Myrtus communis is distilled from the leaves and is useful for dealing with respiratory issues. It also offers antimicrobial and astringent properties. Energetically, Myrtle can help strengthen one’s spirituality and provide support during life changes and transitions.(5)

Woods

Aloes

The Aloes mentioned in the bible is an often misunderstood component. It is not Aloe vera as one might think, as this has no distinctive fragrance. Rather, this aromatic is actually Agarwood or Aquilaria malaccensis, sometimes also called Oud. The heartwood of the Agarwood tree yields the most expensive perfume material in the world. Unlike many other woody plants with aromatic compounds, Agarwood cannot be tapped or the resin collected by incisions in the bark. Rather, the valuable aromatic is produced when the tree (preferably older than 60 years) is

infected with a naturally occurring fungus. In response to the infection, the tree produces an aromatic resin which, over a process of many years makes that section of the wood heavier and darker – and highly valued. The infection occurs in fewer than 10 percent of trees in the wild and its harvest has prompted sustainability concerns, so it is more often sourced from commercial plantations where they deliberately infect the trees. The resin, extracted through steam distillation, requires more than 150 pounds of wood to yield an ounce of oil.(1) Therapeutically, it is used as an antispasmodic and antimicrobial. Energetically, it can help promote mental clarity, balance and calm.(2)

Conclusion

Bordered by the Black, Mediterranean, and Caspian Seas, ancient Armenia stood at the crossroads of three continents and was at various times ruled by Persians, Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, and Mongols. But despite repeated invasions and occupations, Armenian faith, pride, and cultural identity have never wavered, and maintaining our customs through dark times of invasions, persecution, and genocide have helped to sustain our culture and link Armenians around the world. The unbroken tradition of the Holy Muron is just one example of the strength of these customs, and exploring its creation can help deepen our connection with our heritage. The history of its components also serves to illustrate the ancient links between medicine and spirituality, as well

as the importance of aroma in our lives. As Mandy Aftel states so compellingly in Fragrance: “No other sense makes us feel so fully alive, so truly human, so deeply, unconsciously, and immediately connected with our memories and experiences. No other sense so moves us.”(1)

Appendix

| English, as listed (11) | Probable Genus & Species | Plant Family | Armenian Transliteration (11) | Notes | |

| 1 | Balsam oil | Commiphora gileadensis | Burseaceae | Palasan | Balm of Gilead |

| 2 | Olive oil | Olea europaea | Oleaceae | Tzet | |

| 3 | Carnation | Eugenia caryophyllata | Myrtaceae | Mekhag | Correct Translation – Clove |

| 4 | Nutmeg | Myristica fragrans | Myristicaceae | Mshgenguyze | |

| 5 | Sweet Flag | Acorus calamus | Araceae | Pagheshdag | Calamus |

| 6 | Spikenard | Nardostachys jatamansi | Valerianaceae | Hntig Nartos | |

| 7 | Gooseberry | Melastoma malabathricum | Melastomataceae | Sev Peran | “Black Mouth,” Malabar Gooseberry |

| 8 | Cinnamon | Cinnamomum zeylancium | Lauraceae | Tariseng | |

| 9 | Incense | Styrax benzoin | Styracaceae | Khunk | |

| 10 | Cyclamen | Cyclamen persicum | Myrsinaceae | Archedag | |

| 11 | Crocus | Crocus sativus | Iridaceae | Kerkoum | Saffron |

| 12 | Sweet Marjoram | Origanum majorana | Lamiaceae (Labiatae) | Marzanon | |

| 13 | Hors elder | Inula helenium | Asteraceae | Geghmough | Elecampane |

| 14 | Camel’s hair | Cymbopogonschoenanthus | Poaceae | Vaghmeroug | Camel’s Grass, Camel’s Hay |

| 15 | Hazelwort | Prunella vulgaris | Labiatae | Merouandag | Correct Translation – Allheal |

| 16 | Chamomile | Chamamaelum nobile | Asteraceae | Yeritsoug | |

| 17 | Violet | Viola odorata | Violaceae | Manushak buravet | |

| 18 | Water Lily | Nymphaea alba | Nymphaeceae | Nounoufar | Egyptian White |

| 19 | Orange flower | Citrus x aurantium | Rutaceae | Narnchatzaghig | |

| 20 | Allspice | Pimenta officinalis | Myrtaceae | Tarabeghbegh | |

| 21 | Laurel | Laurus nobilis | Lauraceae | Tapnee | |

| 23 | Narcissus | Narcissus poeticus | Amaryllidaceae | Nargiz | |

| 24 | Laurel seed | Laurus nobilis | Lauraceae | Tapnehound | |

| 25 | Laurel flower | Laurus nobilis | Lauraceae | Tapnetzaghig | |

| 26 | Crystal tea | Cistus ladanifer | Cistaceae | Ladan | Rock Rose |

| 27 | Ginger | Zingiber officinale | Zingiberaceae | Godjabeghbegh | |

| 28 | Mastic | Pistacia lentiscus | Anacardiaceae | Mazdakeh | |

| 29 | Musk | Abelmoschus moschatus | Malvaceae | Moushg | Musk mallow, Rose mallow |

| 30 | Hyacinth | Hyacinthus orientalis | Liliaceae | Hagint | |

| 31 | Orange flower water | Citrus x aurantium | Rutaceae | Narinchatzaghigi chour | |

| 32 | Rose water | Rosa damascene | Rosaceae | Varti chour | |

| 33 | Aloes | Aquilaria malaccensis | Thymelaeaceae | Haloueh | Indian Aloe tree, Agarwood |

| 34 | Cardamom | Ellettaria cardimomum | Zingiberaceae | Antridag | |

| 35 | Sandal | Santalum album | Santalaceae | Jantan | Sandalwood |

| 36 | Rose | Rosa damascene | Rosaceae | Vart | |

| 37 | Olibanum | Boswellia sacra | Burseaceae | Gntroug | |

| 38 | Storax | Liquidambar orientalis | Hamamelidaceae | Staghi | Styrax / Oleoresina Styrax |

| 39 | Gallingale | Alpinia galangal | Zingiberaceae | Giberis | |

| 40 | Cubeb | Piper cubeba | Piperaceae | Hntgabeghbegh | |

| 41 | Lavender | Lavandula angustifolia | Lamiaceae | Housam | |

| 42 | Rosemary | Rosmarinus officinalis | Lamiaceae (Labiatae) | Kengounee | |

| 43 | Lemon balm | Melissa officinalis | Lamiaceae | Tor | |

| 44 | Spearmint | Mentha crispa or viridis | Lamiaceae (Labiatae) | Ananoukh | |

| 45 | Wild mint | Mentha longifolia | Lamiaceae (Labiatae) | Taghtz | |

| 46 | Basil | Ocimum tenuiflorum | Lamiaceae (Labiatae) | Rahan | holy |

| 47 | Thyme | Thymus kotschyanus | Lamiaceae (Labiatae) | Tuem | probably wild |

| 48 | Summer Savory | Satureia hortensis | Lamiaceae (Labiatae) | Tzotrin |

Bibliography

1) Aftel, Mandy. Fragrant: The Secret Life of Scent. New York: Penguin. 2014.

2) Ahluwalia, Sudhir. Holy Herbs: Modern Connections to Ancient Plants. New Delhi: Prakash Books India Pvt. Ltd. 2017.

3) Aleksanyan, Alla, Ranier W. Bussman, and George Fayvush. “Ethnobotany of the Caucasus – Armenia,” in Ethnobotany of the Caucasus. European Ethnobotany., edited by R.W. Bussman, 1-17. Cham: Springer, 2017. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-50009-6_18-1.

4) Bezjian, Nigol. Muron. Directed by Nigol Bezjian. Beirut: Mirk Films. 2003. DVD.

5) Bull, Ruah and Joni Keim. Aromatherapy Anointing Oils: Spiritual Blessings, Ceremonies & Affirmations. Petaluma: self-published. 2016.

6) Drobnick, Jim, ed. The Smell Culture Reader. Oxford: Berg, 2006.

7) Dudley, Martin, and Geoffrey Rowell, ed. The Oil of Gladness: Anointing in the Christian Tradition. Collegeville: The Liturgical Press, 1993.

8) Duke, James A., with Peggy-Ann K. Duke, and Judith L. duCellie. Duke’s Handbook of Medicinal Plants of the Bible. Boca Raton: CRC Press. 2008.

9) Foster, Steven, and Rebecca L. Johnson. Desk Reference to Nature’s Medicine. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society, 2006.

10) Ginovyan, M.M., and Trchounian, A.H.. “Screening of Some Plant Materials Used in Armenian Traditional Medicine for their Antimicrobial Activity,” Proceedings of the Yerevan State University, 51(1) (2017), p. 44-53. http://ysu.am/files/SCREENING%20OF%20SOME%20PLANT%20MATERIALS%20

USED%20IN%20ARMENIA.pdf

11) Gulgulian, V. Rev. Fr. Oshagan. “The Holy Muron,” St. Sahag & St. Mesrob Armenian Apostolic Church, November 15, 2015 http://www.sahagmesrobchurch.org/pubs/bulletin/2015-11-15.pdf

12) Harvey, Susan Ashbrook. Scenting Salvation: Ancient Christianity and the Olfactory Imagination. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2006.

13) “Holy Muron,” Armeniapedia.org, accessed October 14, 2018, http://armeniapedia.org/wiki/Holy_Muron

14) Mojay, Gabriel. Aromatherapy for Healing the Spirit. Rochester: Healing Arts Press.1997.

15) Musselman, Lytton John. Figs, Dates, Laurel, and Myrrh: Plants of the Bible and the Quran. Portland: Timber Press, Inc. 2007. http://cccl.enkilibrary.org/EcontentRecord/757.

16) Totilo, Rebecca Park. Anoint with Oil. St. Petersburg: Rebecca at the Well Foundation, 2014. http://cccl.enkilibrary.org/EcontentRecord/53901.

17) Vardanyan, Stella. “Medicine in Ancient and Medieval Armenia,” Armenian History.com, January 13, 2012, https://www.armenian-history.com/19-history/historical