Last night I left a baby on a rock.

Unlike the others, this baby wasn’t detailed – it didn’t drool or coo or make jerky movements or ever-changing expressions. In fact, it wasn’t much different from a doll except that it was heavy, straining my arms as I held it to my chest. I was with friends when I was called away to do something, I’m not sure what, maybe row a canoe or put on a skit. So I laid the baby down on a rock. It was a flat boulder emerging from a field of grass, like the kind people sit on in Central Park. Inevitably, the moment arrived when I realized what I had done, so I rushed back to retrieve the baby only to find that it was gone. I was beside myself with guilt. How? How could I have left a baby? On a rock? I rushed around, trying to locate the lost baby, returning to the rock again and again hoping someone would put it back where they found it, but relief came only when I woke up.

I’ve never thought my life would be incomplete without a kid. It’s not that I’m opposed to having a child; I’ve just always felt that I would pursue the idea only if the right conditions arose, i.e., a loving partner who would take equal responsibility to parent. If this situation doesn’t come along, no big deal. And yet for years I’ve been frantically searching for babies I’ve abandoned on airplanes, in art museums, libraries, and movie theaters. This time, leaving behind the baby on a rock—in the wide open air, on such a hard surface, and among millions of people—felt particularly irresponsible, and the accompanying panic was painfully real.

I actually witnessed a similar scene a few days ago, but I don’t think it was the emotional trigger. I think it’s Seyran. Today he wants me to take some photos of him to send to his parents. I guess they’ve been asking him for pictures, but he hasn’t been sending any lately, because they would hate his long hair now grown past his shoulders since he left Armenia. They would also take umbrage at his full Jesus beard, black with a sunburst of brown underneath his lip, thick and wiry, dense as a woolen carpet. He resembles a Byzantine-era king with an angular beard covered in swirling curls, the kind depicted in profile in bas relief on ancient churches.

To my eyes he is beautiful, but last week Seyran woke from a nap and scared a baby to tears.

My friend Nora was visiting with her son Raffi just as Seyran got up to go to his IT job on the graveyard shift. We were playing with the baby on the floor and I was noticing the clumps of dust clinging to the edges of the Persian carpet when Seyran silently appeared, standing in the doorway. He was sleepy in his shorts and tank that revealed the soft black down covering his shoulders, chest, and legs. Raffi was instantly frightened, pushing himself backward like a crab into the corner of the room. His mom explained in a comforting voice that this man was just Seyran, no one to be afraid of. But the child shuddered as if seeing a ghost. “I think it’s your long hair,” my friend surmised. “He’s never acted this way with anyone.” Strangely, Seyran did nothing to assuage the baby.

It was a striking contrast to the last time they visited. About six months before, Seyran sang lovingly as he cradled the infant in his arms. Nora had told me our time together reminded her of visits to Armenia. I knew what she meant. Seyran played the generous host, roasting fish and vegetables in the oven, serving tea with sweets. It was something I loved about him, and about Armenia, too.

Nora now asked Seyran how he was doing, perhaps to change the tone. Seyran just shrugged and sullenly slumped away. After they left, he said he couldn’t believe how big the baby was, now 9 months old. “How can you call someone a friend when you haven’t seen her for months?” he asked. I gave him the answer that I always do, that friendship is different in New York, but he didn’t ask the question to hear an answer. It obviously troubled him that the baby was now so big, and that Nora hadn’t turned out to be like the kinds of friends we had in Yerevan. “You didn’t have to be rude to her just because she didn’t meet your expectations,” I told him.

“There is no point in talking about my life with a friend who is not really a friend,” he said. I understand his loneliness, but his ire didn’t feel fair. Because I’ve been spending so much time with Seyran, I haven’t been seeing my friends as much. I’ve been trying to give to him the sense of belonging he provided me when I first arrived in Yerevan, unable to speak Armenian, haplessly trying to perform my duty to “give back” as a diasporan writer. I couldn’t interview anyone who didn’t know English, so I couldn’t write. But Seyran introduced me to everyone he knew, from artists in their sixties to punk kids in their twenties. Among this milieu, our seventeen-year age difference didn’t seem to matter to anyone. We invited friends over for dinner, sliced loaves of brown bread, drank vodka, and gossiped for hours. I became immersed in his world. Unfortunately, the middle-aged friendships I offer him here, awkward dinners in loud restaurants, arranged weeks in advance, just can’t compare.

I keep trying to help him find his way, though. A few days after Nora’s visit, we took a long walk around Astoria. We wound up and down side streets of old turn-of-the-century homes covered in aluminum siding next to chains of brick houses built before the Depression. Then we visited a bunch of shops: Chinese, Korean, Greek and Indonesian. He couldn’t experience this ethnic diversity in Armenia, and it is the one thing that still gives him happiness after everything he left behind.

We made our way to Little Egypt for paklava when on a whim he decided to shave off his beard and all of his hair. A stylist in a nondescript salon snipped off Seyran’s 8-inch ponytail in one piece, claiming he would donate it to a charity that crafted wigs for women who lost their hair from radiation treatments. I whispered to Seyran that the stylist could sell it, but Seyran didn’t care. He had grown that hair as an expression of his freedom from the conformity of Armenia, its oligarchs trickling down their corruption and hypocrisy. It represented his queerness – and in a way, mine too, since being bi felt like something we uniquely accepted about the other. Now it was in a zip lock bag, given away virtuously or for profit, we had no way of knowing.

As the buzzer made its way across his face and his head, hair gently sliding off his skin, I flipped through a magazine, getting lost in an interview with Michelle Obama. A few minutes later I looked up, noticing a barefoot toddler, a little girl with dark curly hair, wearing a flowered top and diaper-heavy pink pants. She ambled towards me and stared my way, smiling sweetly. I couldn’t help smiling back. She giggled as the other stylist knelt down beside her and pretended to poke her in the tummy.

“How old is she?” I asked.

“Isn’t she yours?” the stylist replied.

I shook my head. We looked around the room; there were no other customers.

Seyran’s attention was now caught and he peered at us out of the corner of his eye. Another woman who had just swept up his hair from the floor peeked out the door, where the sky was spreading a periwinkle dusk over the neighborhood. No possible moms were out on the block lined with hookah bars, mostly populated by middle-aged men who smoked the pipe.

Eventually, while the stylist played with her, the sweeping woman called the police, though they suspected that the mother was at the mosque up the street and might have lost track of the child. It had happened before. Still, they speculated what would happen if no one came to claim her: “Don’t make me take her,” one of them joked, “All I got in my fridge is a can of Red Bull.”

For a minute I thought about bringing the child home. Here we were, Seyran and I, a couple with a home and a kitchen full of food. Of all the characters in the salon to take care of a baby until the situation sorted itself out, we were the most conventional option.

A few months after we met, after I’d accepted that he was more than a fling, I entertained the thought that we might have a kid someday, along with all the other happy projections into the future one makes at the start of a new relationship. But as our troubles have mounted, I’ve abandoned that idea.

A child must have some agency in my mind, though. It would certainly be welcome news to my parents, still pressuring me to make them grandparents so they won’t have to answer any more judgmental questions at Sts. Sahag and Mesrob Church. My family name would continue, my generation would generate. It’s strange that such an idea still has power as much as I’ve pushed against its demands all my life. I’d be my own queer version of a good Armenian girl.

I felt a hand poke my shoulder and there was Seyran, bald, with no beard, clean shaven and shiny.

*

Since his sleek new look is now acceptable to his parents, Seyran asks me to photograph him. I tell him that I am about to go to yoga—I need to shake off that baby nightmare from last night—but I can do it afterwards. No, he wants to do it now. So I grab my camera and snap one of him.

“No, stop,” he commands. “I want to take some outside with my bike.” This strikes me as incredibly cute. I smile and he says, “Fuck you, I’m not doing it for myself but for my parents.”

“I’m not laughing at you,” I defend myself.

He snaps. “Forget it, I don’t need your help.” He bounds down the stairs and takes the photos on his own, presumably using the self timer. When he comes back in, he has trouble transferring the images to his computer. I offer to put them on mine and email them to him. “No, I told you. I don’t want any help from you.”

“What’s wrong?”

“You should know.”

I sigh. “That’s passive aggressive.”

“What does that mean?”

Without a way to translate, I scour my mind for the reason for his feelings. Perhaps it’s because his behavior makes no sense that I look to answers within myself. I still believe that I did the right thing in bringing him here to escape the army. It’s just that I’ve been working a lot with the semester starting, so I’m more stressed than usual with less time to pay attention to him. Maybe this is what’s troubling him.

As I leave for yoga, I apologize if I’ve done something wrong. He says, “You don’t understand; it’s your attitude the last few days. When I’m unhappy or stressed I don’t put it onto you, but you do this to me.” I’m not sure how I have put my stress onto him. And it doesn’t occur to him that he is now putting his feelings onto me. Rather than get into a blame-game, I tell him, “Maybe you could give me some space when I am stressed.”

He looks at me with resignation and says, “Never mind.”

When I come home from yoga, I ask if he wants something to eat. He declines since he’ll be leaving for work soon. I proceed to make green beans and tomatoes with bulgur in the rice cooker. As I am chopping, he takes some chick peas out of a container in the fridge and starts popping them raw into his mouth. “I thought you weren’t hungry,” I say.

“You’re cooking these things and it makes me hungry.”

“Well, put that away and eat this.”

“I don’t want to eat with you,” he says.

He is naked, and with his bald head he looks like a big baby.

“Well, leave then!” I snap. “You’re making me feel worse when I’m just trying to be nice to you!”

“You’re not nice to me,” he says.

We go back and forth like this. It’s almost like our dialogue is scripted and I have to recite my part: like when you’re in a play and you proceed with the scene even though it’s going terribly wrong. We have performed the same bad act so many times that it feels like the pattern has carved a new groove in my brain. Perhaps it was always there to begin with.

While he’s in the shower, I follow the neural pathway and ask if he wants me to scrub his back. He says no. A few moments later, I return to the bathroom and ask if he needs a towel. He is already wrapped in one and says, “You don’t give me a towel when I need it and then you try to give me one when I don’t need it.”

I burst out laughing. He is a caricature of a king, like the kind from the bas-relief. During my year in Armenia, I visited so many ancient churches, carved with benefactors and priests, not to mention countless images of symbolic flora and fauna: pomegranates, grapes, tigers, and eagles. I touched them with my hands, thinking about the artist stoneworkers who had carved them eons ago. As a descendant of genocide survivors who often felt like my culture existed in negative space, I appreciated the hardness of the stone: here was proof that my people existed.

Now I am erased: nothing pleases him; nothing I do is right. I must draw so much of my self-worth from helping him, that when he takes away the opportunity to care for him, I completely lose it. Unfortunately, I cannot leave him. I have tried, but it goes against everything I have been taught to not turn an Armenian out. The military would kill him, the way they haze soldiers to death, then blame suicide. I could never imagine what they would do with a queer kid.

Breaking up with Seyran feels like walking away from my culture—one that I am still trying to piece together, understand, and embrace. It’s not lost on me that I’m trying to fill something in with him, like his Armenianness makes up for my lack. But I also believed a relationship with a younger guy would be more egalitarian. I’ve insisted my whole life on an equal partner, someone who would fairly share the labor of raising a child, and yet what have I done but get myself lost in a relationship in which I am some kind of a mother.

Seyran walks out of the bathroom to get ready for work and I hold back a sob, swallowing it inside me. I nearly choke, air passages blocked.

“This always happens,” I remember the stylist complaining at the barber shop. “Why can’t they watch their kids?” The child I fleetingly thought to adopt didn’t seem aware that she had been abandoned. She had discovered a whole new world in the salon, smiling and giggling with glee. Eventually, the mosque let out, and the stylist brought the child outside to see if she would be claimed.

Dusk deepened to night and a small crowd of people gathered in front of the salon. Suddenly, I heard a wail. There was the mother, in a black flowered headscarf. She scooped up the baby into her arms, her oval face wracked with grief, eyebrows arched in pain. According to a henna-bearded man standing next to me, she had been searching for her throughout the mosque, then on the street till she arrived at the salon. Though her baby was now in her arms, she was beside herself, sobbing uncontrollably. I felt for her, recovering from her panic and grieving her separation from her sweet child.

From my bedroom I hear Seyran walk down the stairs and slam the front door to go to work. The house is quiet, and I can breathe again. But I still can’t release any tears.

I envy that mother, crying over the horrible loss that could have been.

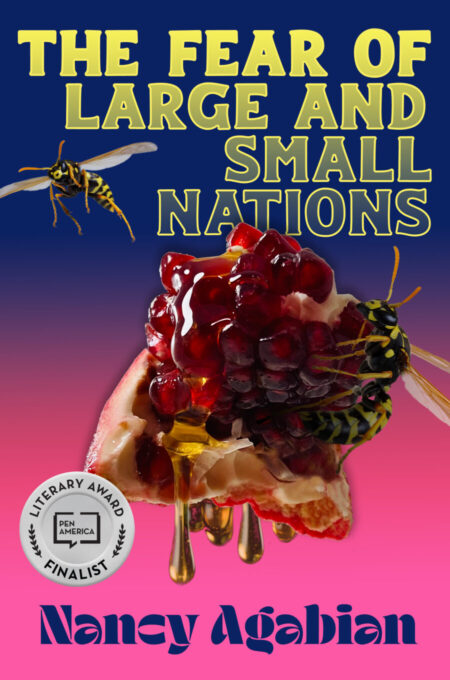

This piece is an excerpt from The Fear of Large and Small Nations by Nancy Agabian, which will be published by Nauset Press on May 9th. You can find more information and purchase the book here.

Nancy Agabian’sprevious books include Me as her again: True Stories of an Armenian Daughter (aunt lute books), a memoir honored as a Lambda Literary Award finalist for LGBT Nonfiction and shortlisted for a William Saroyan International Writing Prize, and Princess Freak (Beyond Baroque Books), a collection of poetry and performance art texts. In 2021 she was awarded Lambda Literary Foundation’s Jeanne Cόrdova Prize for Lesbian/Queer Nonfiction. The Fear of Large and Small Nations is her first novel. For more info: nancyagabian.com.